Globosat Play is a video product for pay TV subscribers, where you can catch up programs you missed on TV. It’s like an umbrella for a couple of different channels. One of the most popular of them is SporTV, one of the largest sports channels in Brazil.

Last year we had the Olympic Games, a major sports event here in Rio. As SporTV channel was going to have a large coverage for the event, we decided to rethink the user experience for SporTV Play (SporTV channel offers inside Globosat Play). In this case, we were going to focus in improving the live TV experience, which is responsible for most of the audience.

Besides rethinking the user experience, we decided to also rethink our front-end architecture, and address a couple of the issues we had.

I’ve already written about Globosat Play architecture before. Its front-end is basically a couple of Rails apps using regular erb templates. These apps share components through a component library called globotv-ui. It’s about 4 years old, way before newer component technologies arised and got popular.

As descripted in the previous post, this component library solution allowed us to avoid rewriting the same components again and again for each app. We were able to share our components, but the main problem is that this was an in-house solution. We defined our components structure to attend our needs, so it was really hard to share them outside our product.

Also, we had a few problems with our front-end architecture. When we updated a component that was used on pages served by different apps, we needed to “synchronize” the deploys. If we deployed one app and took too long before deploying another, in the mean time, both would have different versions of that component. That could generate an inconsistency for our product, and it was one of the issues we wanted to address with the new solution.

In late 2015, we started a couple of technical discussions and some proofs of concept, and decided to adopt React in our front-end. A couple of arguments led the way to our decision:

Standardize components structure

Even after creating a dozen components in globotv-ui, we still could find some differences among them. That’s because the structure is loose and not well documented. Usually we start a new component looking at another one, and replicate that structure. But a lot of different developers worked on that library, each one with his own preferences. So we really didn’t have a pattern for components. They were well organized and tested, but in the end, they were just a couple of JS and CSS files, sometimes with a template for generating the HTML (in Handlebars for client-side rendering, or ERB templates with Rails helpers for server-side).

The clear and well known React component structure helps keeping a pattern among components. The component lifecycle lets us manage how our components should behave. It allows us to not only open source a couple of generic components, but also search for ready components instead of recreating everything we needed.

As an example of this, we wanted to keep our header sticky after the user scrolls down the page. Instead of implementing this behavior, we used react-headroom. Problem solved!

Declarative programming model

Another benefit that React brings is its declarative programming model, instead of the traditional imperative model. Here is a simple example: a text area with a “Tweet” button, which should be disabled while the text area field is empty. Here is the imperative implementation using jQuery:

// Initially disable the button

$("button").prop("disabled", true)

// When the value of the text area changes...

$("textarea").on("input", function() {

// If there's at least one character...

if ($(this).val().length > 0) {

// Enable the button.

$("button").prop("disabled", false)

} else {

// Else, disable the button.

$("button").prop("disabled", true)

}

})

Now the React version:

class TweetBox extends Component {

state = {

text: ""

}

handleChange(event) {

this.setState({ text: event.target.value })

}

render() {

return (

<div>

<textarea onChange={this.handleChange}></textarea>

<button disabled={this.state.text.length === 0}>Tweet</button>

</div>

)

}

}

Globo Play release

The third strong argument in favor of React was the release of Globo Play, in late 2015. It’s another video product developed here at Globo.com. It’s very similar to Globosat Play, and it already used React. So when we started developing the new interface for SporTV Play at the Olympic Games, the team that developed Globo Play already had a great experience with it to help our adoption.

The new architecture

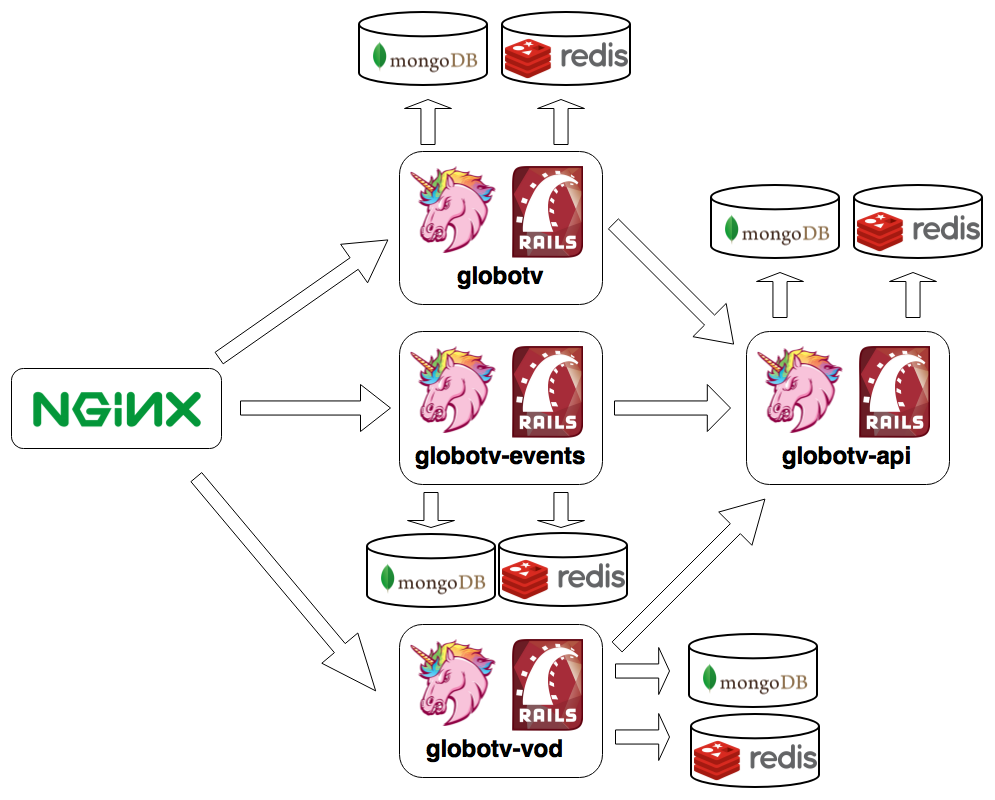

As descripted in a previous post, our architecture was already microservices-based:

In the front-end, we had a couple of different apps to serve different pages in our product, with an nginx server in front of them. The nginx server proxies the requests to each app, according to the request path. Our idea was adding a new rule to it, to forward all requests to SporTV Play home and live signals pages to a new app. This new project was going to use React, and ideally share components with Globo Play.

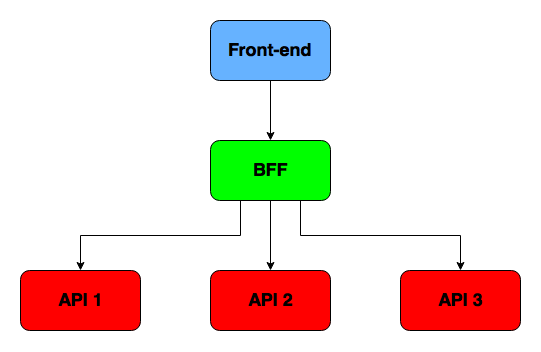

The first step was thinking about the API for this new front-end app. We already had a couple of APIs serving our current apps, so we didn’t need to create a new API. We could just use what we already had, but we decided to follow the Back-end for Front-end pattern.

The APIs we already had served well many of our apps, and some of them are legacy. They have a lot of services, and most of them are fine-grained. To serve the new front-end app, we would probably need to make many requests to group all the data we needed.

Also, we thought it was a good idea to separate the new app from the old ones. Doing this, we would have less chance of coupling old and new apps. Suppose both of them consumed the same services; that would create a coupling between them. If the new app required a change in this service contract, we wouldn’t be able to do that without the risk of breaking the old app.

Besides that, we know the mobile consumption is raising, and sometimes we suffer with terrible 3/4g connections. With a new API specifically designed to attend the needs of the new app, we could deliver the smallest possible payload (just the data we were going to use). Also, we could create more specific services, reducing the number of requests to a minimum.

We followed two principles from the Back-end for Front-end (BFF) pattern: the front-end consumes services from its BFF and nothing more; and the front-end is the only BFF client. They are tightly coupled together, but this is not a problem, because they should both be maintained by the same team. It’s like we are splitting our app in two. The BFF is responsible for orchestrating requests from internal, fine-grained services, apply some business rules and deliver data ready to be consumed by the front-end, which just consumes these coase-grained services and takes care of the presentation layer.

One downside of the BFF is code replication. Some of the services we created in the BFF were new and very specific to our new SporTV Play front-end app (like the current schedule and the list of live signals). Others were already available in our internal APIs. But to follow the rule were the front-end can’t access any service outside its BFF, we needed to add a new route to the BFF, and basically make a proxy pass to our internal APIs. As any decision in software engineering, it’s a tradeoff. There is no perfect solution for everything, and the benefits overcome this issue.

For more details and discussions about the BFF pattern, check out Sam Newman’s and Phil Calçado’s articles.

This is the first post of a series. In the next ones, I intend to write a little more about React components, state management, CSS architecture and components sharing.