Code review is an amazing tool to improve code quality. It brings many benefits, to the reviewer, to the reviewee and to the team.

How we do code reviews

To add code reviews to your team workflow, first you need to use a version control tool. If you don’t, start with that.

Basically, the idea is never committing directly to the master branch - or whatever other branch you choose as the main one, but usually it’s the master branch. To start any changes to the source code, be it a new feature, refactorings or bugfixes, you need to create a new branch. You can also create conventions for the branch names, but this is not required.

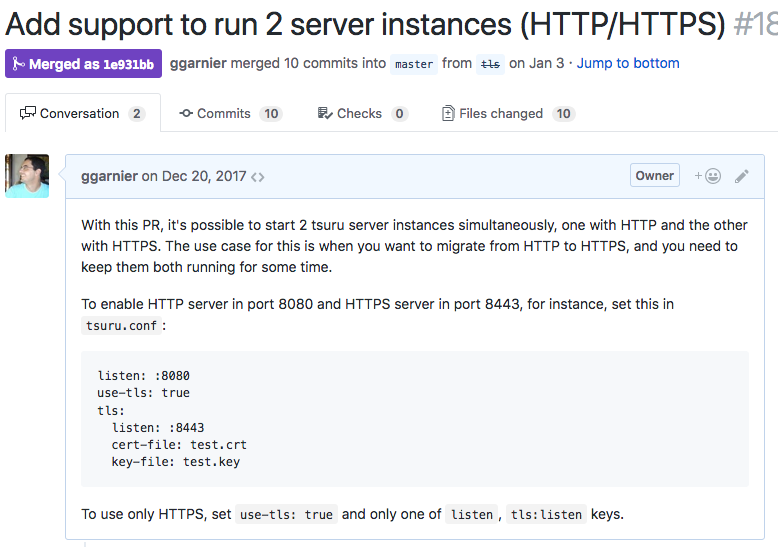

After you finish working on your own branch, you can trigger the code review process. If you use a repository manager like GitHub or GitLab, they already provide tools to help on this process: GitHub calls them pull requests, and GitLab, merge requests - to make it simpler, I’ll call them change requests from now on. You can add some comments explaining the purpose of the proposed changes, and maybe links to other related change requests or issues. These are very important to make the objective of that change request clear for everyone that might review your code. When in doubt, be as specific and clear as you can. Here’s an example from tsuru, the project I currently work in: a pull request with a detailed description.

As soon as a change request is created, it’s available for any other member of the team to start reviewing it. You can also assign it to a specific person, if you think his/her opinion is important - maybe when you change a specific and obscure part of the project that not everyone dominates.

As a reviewer, you job is to check many aspects of the code. Here’s a non exaustive reference list:

- accuracy and completeness: does the code do what it’s supposed to do?

- bug free: doesn’t it introduce new bugs (like not handling corner cases)?

- expressiveness: is it clear on its intentions? Can a reader clearly understand the coder’s objectives?

- scalability: could it handle the expected load?

- conventions and standards: does it follow the agreed conventions for code style, file and directory structure, etc?

- tests: do the tests cover all the use cases, including important corner cases? Is there a specific use case that deserves more tests?

After checking the code, the reviewer can basically accept or reject it - GitHub also allows you to add review comments without explicitly approving or rejecting. When you approve, that means you think those changes could be promptly merged to the main branch. But when you reject, that could mean you doesn’t agree with that change at all (e.g. you don’t think this software should have the proposed feature), or that you’re requesting some changes to the code. That’s what review comments are meant for.

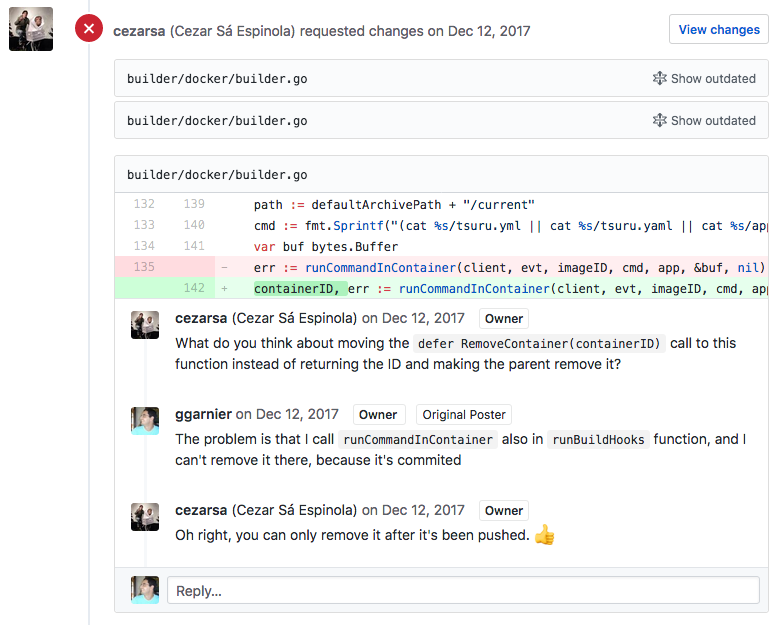

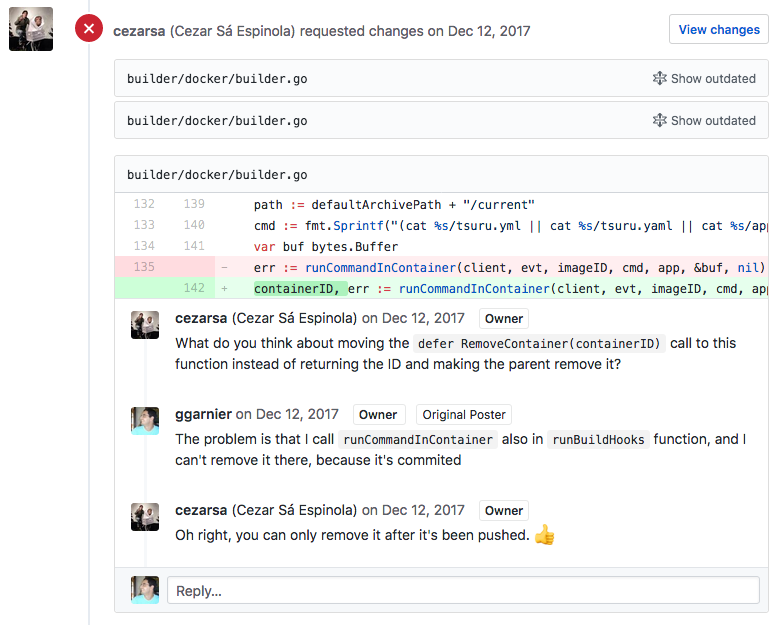

Usually a review comment can be added to a specific line or code block. That could be a typo, a function you think should be named differently, a bug you spotted or a missing test or documentation. The comments should make this clear to the reviewee, who can reply to the comments or make requested changes. Then, this process repeats until the change request gets approved.

When the reviewer accepts the proposed changes, the reviewee has two options: merge/rebase the changes to the main branch and finish the code review process, or ask for another developer review. This is the case when the change is very complex and you’re insecure you may be missing something. When this happens, the review process doesn’t finish until all reviewers accept the changes.

To illustrate, here’s another example of code review from tsuru: in this pull request, I received a couple of comments with request changes. For most of them I changed the code according the suggestions, and one of them generated a small discussion. What’s best is that the discussion is documented in the pull request, for anyone to read and participate.

Benefits of the code review

A code review process brings a lot of benefits to the reviewer, to the reviewee and to the team as a whole:

For the reviewer

- learn about the changes: if someone commits directly on the main branch, only the author would know the details about it. When you review, you also get to know what those changes do, how and why they were written. And if you don’t understand, you have the opportunity to ask for more information

- learn about the project: if you are new in the team, code review is a great tool to obtain knowledge about the project. Even if you still don’t understand the project, go ahead and review everyone’s code, just to start understanding it a little better

- learn about the technologies involved (languages, frameworks, libraries): just like when you’re new to the team, if you are getting started with the tech stack used in the project, you’ll benefit even more from reviewing people’s code. You’ll learn about the language’s features, new libraries to solve common problems and features of the frameworks the project uses

- develop a critical view of someone else’s code: if you are an inexperienced developer, you probably have a hard time trying to spot problems in someone else’s code. After code reviewing a couple of times (and checking other developer’s reviews), you’ll learn how to be more critic. And what’s more important, you’ll learn that criticizing someone else’s code is not offensive, it’s actually a good thing, an opportunity for them to learn. And you’ll learn with the other’s mistakes. That’s why junior devs should review seniors’ commits

For the reviewee

- learn about the project: just like the reviewer, a great way to start in a new project is asking for feedback from the more experienced in the team. Here’s another example

- learn about the technologies involved (languages, frameworks, libraries): the same comments from the reviewer part are worth here. Here’s one more example

- learn other ways to solve problems: when you face a bug, you may already have the complete solution in your head; that solution could really work after you implement it. But that doesn’t mean this is the only way to solve the problem. Probably there are other solutions out there, and they may be simpler, clearer, safer or perform better. Other developers could show these other solutions in their reviews

- learn to accept critics: sometimes we get so attached to the code we wrote that we could get offended when someone criticizes it. Code reviews help us learn to get over this, because we are explicitly asking for people to give feedback on our code, and they’ll answer. Over time you’ll learn these feedbacks are great ways of learning

For the team

- shared code ownership: now two or more people are responsible for the code one of them wrote - by the way, that could also be reached with pair programming. Shared code ownership is great after a bug is released into production: the developer who wrote the code is no longer the only responsible for that. This also helps reaching a blameless culture

- helps keeping standards: if the team agreed on specific conventions, like code style rules, tests for every line of code or document all the APIs, code review is a great way to make people monitor each other on these

Common problems and concerns

Won’t this slow me down?

When we suggest that our team starts working with code reviews, people usually get apprehensive about this process making the team slower. If they’re used to finish their work, push the code and deploy to production, they may have this concern.

In fact, you won’t have that fast dev-to-production cycle. But that is a small downside against the many benefits presented above. It’s a trade-off, like every decision you make in your project.

One common concern is having to wait for a long time for another dev to start the code review process. If people still don’t see value in this process, they indeed may not prioritize this. But as soon as you get to be on the other side - waiting for other people’s reviews -, you’ll start giving it more attention. It’s an organic process that usually regulates itself.

How to handle large change requests?

Another problem is when the change request is very large. This will require more time from the reviewers, and it may be harder to analyze: you may lose focus during the review.

Just like on the previous item, this should be self regulated. If you start making very large change requests, you’ll learn they aren’t much productive when someone else asks for you to review a large change request.

There isn’t an ideal size of change request. But you should make them as small as possible. If you’re working on a complex feature, you may try splitting it in a couple of small change requests, independent from each other. But if you can’t make them independent, an alternative is starting with a branch forked from the main one - you may call it feature-something, then creating other branches from it. As you finish each part, make the change requests to merge to you feature branch, not the main branch. And only when you finish every “sub-feature” change request, only then you merge your feature branch to the main one.

When not to use code reviews?

Finally, another common question is: are there exceptions to the “never commit to the main branch” rule? If the change is very simple and small, won’t the code review process be just a formality?

In fact, there are a couple of situations where you may bypass the code review process. One example is updating a dependency version. But I still think it’s worth opening the change request, to make other team members aware of the changes. But this kind of decision is up to the team, and should be accorded among them.

To finish, I suggest reading this great post about how to conduct effective code reviews.