Handling HTTP cache is one of the most important aspects when you need to scale a web application. If well used, it can be your best friend; but when badly used, it may be you worst enemy.

I’m not going to explain the basic aspects of caching here, there are already a lot of great material about it. I’m going to bring a specific problem here.

On a previous post, I wrote about Globosat Play architecture. As explained there, it evolved to a microservices architecture, and as such, we ended up making a lot of HTTP requests to our internal services. So we needed to manage those requests very well.

Suppose you access a page like Combate channel home page. To fill up every information in that page, we need to query data from:

- a videos API, to bring up a list of available channels and the latest videos from Combate channel

- a highlights API, to check the latest highlights selected by an editor

- an events API, to check a list of previous and next UFC events

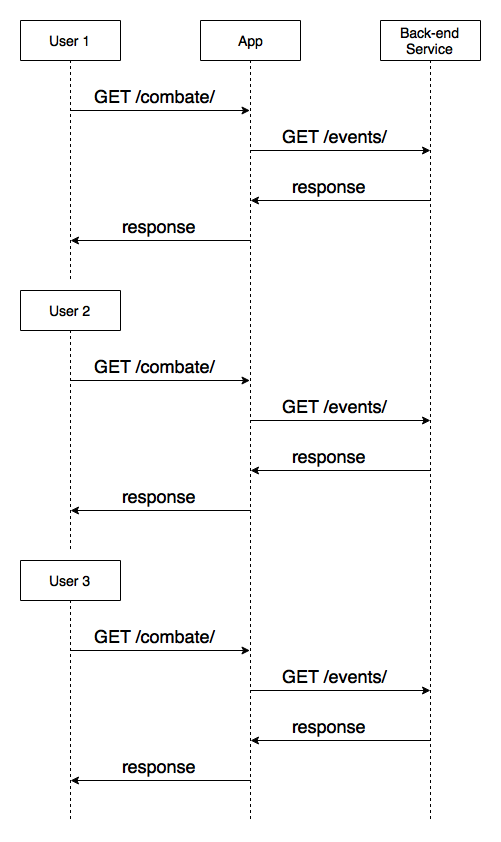

That means a user request could be represented by something like this:

Now imagine one of these services is unavailable. Or very slow. Or giving un unexpected answer. If we didn’t consider these scenarios, we would end up with a brittle application, susceptible to a lot of issues.

Michael Nygard, in Release It!, says we must develop cynical systems:

Enterprise software must be cynical. Cynical software expects bad things to happen and is never surprised when they do. Cynical software doesn’t even trust itself, so it puts up internal barriers to protect itself from failures. It refuses to get too intimate with other systems, because it could get hurt.

That means we shouldn’t trust anybody. Don’t assume a service is up, available, fast and correct. Even if you know and trust the maintainers of this service, consider that it may have problems (and it will, eventually!). One of the defense mechanisms against this is caching.

At Globosat Play, we decided to implement two levels of cache. We call them performance and stale.

Performance cache

The performance cache is meant to avoid a flood of unnecessary requests to a single resource in a short period of time. Going back to Combate home page example, one of the services our back-end requests is a list of next UFC events. This doesn’t change often; only when a new event is created, or when an event finishes, once a couple of weeks. That means, it’s very wasteful to hit that service for every user accessing Combate home page. Suppose the events API response changes once a week; if that page gets 100,000 hits in that period, that means I would make 100,000 requests for that API, when I could just make one and keep the results in cache, which is much faster.

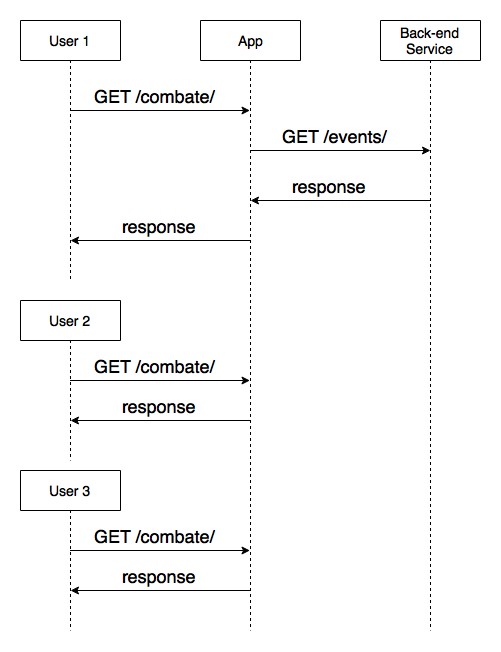

The solution for this is keeping a performance cache for a specific period of time. Suppose I set my cache for 5 minutes. The decision flow for this would be:

- cache available? Respond with cache

- cache unavailable? Make the request, write the response in cache, set its TTL (Time-to-leave) for 5 minutes, respond

That means I would hit that API only once every 5 minutes, independenly of how many users are accessing my home page right now. I’m not only avoiding wasteful requests, but also protecting my internal services and giving faster responses - it’s much faster to access the cache than making an HTTP request. The diagram below depicts this scenario:

The problem in this scenario is, even if I’m sure that my events API only changes once a week, I can’t set my cache TTL for 1 week. Imagine if I do that and the cache expires a few minutes before a new event is registered. That means I won’t see the new event until the next week! You need to carefully evaluate the performance cache times for each service you depend on.

Even if you have a service that can’t be cached for that long, you could have a great benefit from caching the request for at least a few seconds. Imagine an application with 10,000 requests/s. If you set the back-end service request cache TTL for 1 second, you are making a single request for your service, instead of 10,000 requests!

Stale cache

The second cache level is stale. It’s a safety against problems like network instability or service unavailable. Let’s use the latest videos API as an example. Suppose my application back-end tries to access this service and it gets a 500 HTTP status code. If I have a stale cached version of it, I can use it to give a valid response to its client. The stale data may be outdated by a few minutes or hours, but it’s still better than giving no response at all - of course, that depends on the case. For some kinds of services, an outdated response may not be feasible, like giving the wrong balance when your client accesses his bank account. But for most of the cases, stale cache is a great alternative.

Usually we set the performance cache time for a few minutes and the stale cache for a few hours. Our standard setup is 5 minutes and 6 hours, respectivelly.

Implementing cache levels in Ruby

To implement performance and stale cache levels in Ruby applications, we created and open sourced a gem called Content Gateway. With it, it’s much easier to manage cache levels.

After installing it, you need to configure the default request timeout, the performance and stale cache expiration times and the cache backend, besides other optional configurations:

config = OpenStruct.new(

timeout: 2.seconds,

cache_expires_in: 5.minutes,

cache_stale_expires_in: 6.hours,

cache: ActiveSupport::Cache.lookup_store(:memory_store)

)

gateway = ContentGateway::Gateway.new("My API", config)

With this basic configuration, you can start to make HTTP requests. You can also override the default configurations for each request:

# Params are added via query string

gateway.get("https://www.goodreads.com/search.xml", key: YOUR_KEY, q: "Ender's Game") # => "<?xml version=\"1.0\" encoding=\"UTF-8\"?>\n<GoodreadsResponse>\n <Request>..."

# Specific configuration params are supported, like "timeout" and "skip_cache"

gateway.get_json("https://api.cdnjs.com/libraries/jquery", timeout: 1.second, skip_cache: true) # => {"name"=>"jquery", "filename"=>"jquery.min.js", "version"=>"3.1.1", ...

It supports POST, PUT and DELETE as well. For all verbs, there are two methods for making the request: one is simply the name of the verb and the other has _json suffix. The former treats the response body as string, and the latter, as a Hash.

gateway.post_json("https://api.dropboxapi.com/2/files/copy", headers: { Authorization: "Bearer ACCESS_TOKEN" }, payload: { from_path: "path1", to_path: "path2" })

gateway.put_json("https://a.wunderlist.com/api/v1/list_positions/id", payload: { values: [4567, 4568, 9876, 234], revision: 123 })

gateway.delete("https://a.wunderlist.com/api/v1/tasks/id")

You can also make a few other customizations. Check out the project page on github for more information and examples.